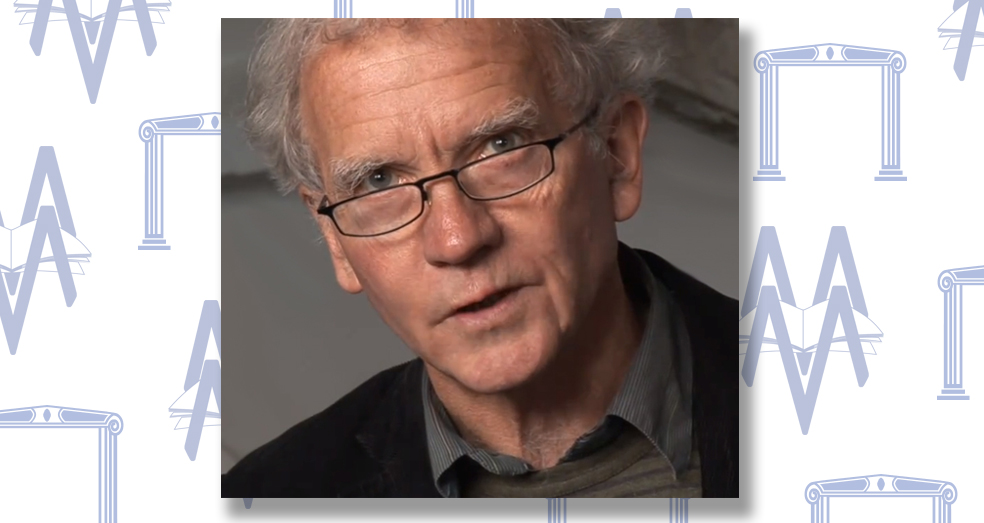

David Constantine

Notes on entering the Michael Marks Greek Bicentennial Poetry Pamphlet Prize

I have addressed the following notes and warnings to myself over many years of writing poetry. I applied them equally to poems complete in themselves and to others belonging together in sequences. So I hope what I say might help you now as you write poems to be presented in a portfolio and having a common topic.

Strictly speaking, it isn’t possible to say in advance what a reader might be looking for in a new poem. It’s in the nature of a good new poem that in some degree it will be surprising. A great new poem will effect some alteration, however slight, in the hopes or expectations we invest in the reading of poetry altogether. So if I list a few things I might be looking for in the submissions for this new prize they do not at all amount to a prescription. The best poems will have in them something that could not be foretold or prescribed.

It’s perhaps easier to say what wouldn’t be welcome than what would. Poetry is not a zone in which it is OK to stop thinking and start feeling. Altogether the opposition of thinking and feeling is false. A poem in its workings should be just as rigorous as a report on a new vaccine or on the cladding of high-rise flats. The thinking-feeling in a poem must be exact – even in its ambiguities, even in its variety of possibilities. Rilke stated categorically: ‘A poet hates approximations.’

Some scepticism is advisable while you are writing a poem and especially when you think you have finished it. You need a friendly devil sitting on your shoulder, to ask politely, ‘Are you quite sure that’s what you mean?’ Or rudely mutter, ‘Oh come off it!’

Avoid abstractions. Brecht had a reminder in capital letters pinned up above his desk: TRUTH IS CONCRETE. The original sense of the word ‘idea’ is form, a shape, a thing seen. Best to begin a poem only when you can see the start or a major part of it as a concrete image. Memory and Imagination are sister faculties. Remembering as concretely as possible some sight or experience – a tree, an animal, a face, an encounter – is most often a good way in. And a tone of voice … It is never good to address the human race, or posterity or futurity, or Hope, Despair etc. Don’t shout. Think of an addressee, real or fictitious (but nobody or nothing lofty), and modulate your tone of voice accordingly.

Shape. It is not possible for a poem to have no shape but the shape you give it may be ugly or beautiful, effective or useless. Shape, form, should never be thought of as separate from ‘content’. Form is the making palpable of the poem’s subject and sense. Discipline is essential. Rhyming, using a regular metre in stanzas, is one kind of discipline (part of the poem’s rigour), but you will not liberate yourself by doing without such traditional means. You will have to devise others, discover their laws and possibilities. For example, if you use unrhyming lines of varying length in no fixed metre, where you break the line becomes critically important.

Best of luck! Nothing I’ve said here is prescriptive. The good poem will be in some way surprising.